SOME HISTORY...

The opening of the first public music school in Udine goes back to 1826: a new association called the "Udine Philharmonic-Dramatic Association" brings together -since then-, along with the most important members of the local aristocratic families, the citizens who love music and theater. The first location was by the premises above the City Loggia where, in addition to a hall for entertainments and a stage, five rooms for the various activities of the Society, particularly for teaching, are obtained. During the first three years, the authorities are unable to start the music lessons, and the only activity carried out by the association is to organize philharmonic and amateur-actors entertainments; in 1830 it was decided to change the name of the association from "Udine Philharmonic-Dramatic Association" into "Institute", pointing therefore out the basis and the primary purpose of the association, which remained that of music education. In 1831, after regular competition, the following teachers have finally been nominated: a music instructor (singing teacher), Giuseppe Magagnini Marche (Montecarotto, 1802-1885), and a professor of violin, the Friulian Giacomo De Sabbata (Cividale, 1800 - Udine, 1840). In this way, the regular lessons could finally begin, while the regular evening performances of musicians and actors were continuing.

The opening of the first public music school in Udine goes back to 1826: a new association called the "Udine Philharmonic-Dramatic Association" brings together -since then-, along with the most important members of the local aristocratic families, the citizens who love music and theater. The first location was by the premises above the City Loggia where, in addition to a hall for entertainments and a stage, five rooms for the various activities of the Society, particularly for teaching, are obtained. During the first three years, the authorities are unable to start the music lessons, and the only activity carried out by the association is to organize philharmonic and amateur-actors entertainments; in 1830 it was decided to change the name of the association from "Udine Philharmonic-Dramatic Association" into "Institute", pointing therefore out the basis and the primary purpose of the association, which remained that of music education. In 1831, after regular competition, the following teachers have finally been nominated: a music instructor (singing teacher), Giuseppe Magagnini Marche (Montecarotto, 1802-1885), and a professor of violin, the Friulian Giacomo De Sabbata (Cividale, 1800 - Udine, 1840). In this way, the regular lessons could finally begin, while the regular evening performances of musicians and actors were continuing.

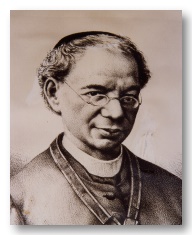

In 1837 the amatuer-actors activity ends, and the school changes its name into "Udine Philarmonic Institute". Starting from 1838, the headmaster of the school is Francesco Comencini (Mantua, 1792 - Udine, 1864), who will then always be working in Udine, with the exception of a shutdown of the Institute which lasted from 1848 to 1857. After his death, the direction passed to Maestro Antonio Traversari (Ravenna 1814 - Moimacco 1887) and Maestro Alberto Giovannini (Brazzano, Gorizia 1842 - Milan, 1903). Starting from 1876, the Municipality of Udine takes direct management of the school, favouring in particular the study of wind instruments, in order to form the city band. The school is radically renewed after World War I, with director Mario Mascagni (San Miniato, Pisa, 1882 - Bolzano, 1948), moving from the premises of "via della Posta" (Post street) to the definitive headquarters in the "Ottelio mansion". In 1922, the school is named after the Friuian musician Don Jacopo Tomadini (Cividale del Friuli, 1820-1883) and, by decree of 1925, we see the equalization of the Musical Institute. The definitive transformation into State Conservatory of Music takes place in 1981, and the expansion of the workforce have led the school to be the most important musical institution in Friuli.

"PALAZZO OTTELIO"

THE SEAT OF CONSERVATORY “JACOPO TOMADINI”

The first news and reports about the building that is the home of Conservatory of Music "Jacopo Tomadini" date back to the mid-sixteenth century, precisely to the year 1555, when the noble Andrea Dolfin Banco, a Venetian patrician, built a stone bridge that crossed the canal near his house, giving the area an almost Venetian look. The building was therefore already existing, and indeed it can be assumed that it was just built around the year 1550, even because important decorative and remodeling works date back to a few years later. There is no other news until 1616, when the building was inhabited by a certain Gio. Martino Bonecco, belonging to a family who had a draper's shop in the prestigious Mercatovecchio street. In 1656, however, his nephew Alvise Bonecco sold the building to the noble Ottelio, who already owned lands that were used for vegetable gardens bordering the properties of the Seminary (to be honest, there is some confusion in the documents, and it seems that the Ottelio family lived here in 1616, and that Boneccos were simple tenants). The Ottelio family was a prestigious family, both politically and economically; in 1772 they found themselves directly involved in the work of enlargement of the seminar requested the Archbishop Gian Girolamo Gradenigo. For the "relief of the young people" and with the aim of creating new spaces for recreation, adapting to the demands of the Ottelios ,who wanted to sell the whole property, the gardens -as well as the house of the Ottelios- were sold. However, being the building of the house too far away, it was not included in the work of enlargement of the Seminary, and was eventually leased. In 1786, for example, the Moroldis moved in there. They had sold their house in the central Grazzano street to the family Asquini Contrini, who probably lived there up to the beginning of the nineteenth century. But, after 1808, even this building followed the fate of the Seminary, which fell in complete command of the soldiers, and had been converted into a military hospital. For a century or so there are no news about the building, which has become property of the Municipality, and that was used as a military laundry and disinfection place during World War I; simultaneously, the little house next door, which overlooks "vicolo Porta", becomes home of the "Night Asylum", founded in 1894. In 1920, the former Ottelio house was finally designated as the home of the Institute of Music. The first lessons took place in 1921, and the following year the building was customized, according to the new requirements. The simple sixteenth century architecture of Ottelio palace has nothing special, but the environment sorrounding it (the canal, the trees) and the clear measurability of its outlines make it look very fascinating. The most outstanding element is the three-light window with the two side arches and the central arch, complemented by a stone balustrade that, supported by four sturdy shelves, almost seems to smash the austere and simple portal below. Inside, there is a good sized central hall, nowadays called "Vivaldi concert-hall", with a Sansovino truss and leaded glass windows. The recent restoration works, completed in 1997, as well as restoring the building to its ancient splendor, have allowed the recovery of valuable archaeological finds, such as pieces of ceramic tableware, Renaissance glasses and a thousand fragments of slipped tiles, etched and painted, dating back to the sixteenth century.

The first news and reports about the building that is the home of Conservatory of Music "Jacopo Tomadini" date back to the mid-sixteenth century, precisely to the year 1555, when the noble Andrea Dolfin Banco, a Venetian patrician, built a stone bridge that crossed the canal near his house, giving the area an almost Venetian look. The building was therefore already existing, and indeed it can be assumed that it was just built around the year 1550, even because important decorative and remodeling works date back to a few years later. There is no other news until 1616, when the building was inhabited by a certain Gio. Martino Bonecco, belonging to a family who had a draper's shop in the prestigious Mercatovecchio street. In 1656, however, his nephew Alvise Bonecco sold the building to the noble Ottelio, who already owned lands that were used for vegetable gardens bordering the properties of the Seminary (to be honest, there is some confusion in the documents, and it seems that the Ottelio family lived here in 1616, and that Boneccos were simple tenants). The Ottelio family was a prestigious family, both politically and economically; in 1772 they found themselves directly involved in the work of enlargement of the seminar requested the Archbishop Gian Girolamo Gradenigo. For the "relief of the young people" and with the aim of creating new spaces for recreation, adapting to the demands of the Ottelios ,who wanted to sell the whole property, the gardens -as well as the house of the Ottelios- were sold. However, being the building of the house too far away, it was not included in the work of enlargement of the Seminary, and was eventually leased. In 1786, for example, the Moroldis moved in there. They had sold their house in the central Grazzano street to the family Asquini Contrini, who probably lived there up to the beginning of the nineteenth century. But, after 1808, even this building followed the fate of the Seminary, which fell in complete command of the soldiers, and had been converted into a military hospital. For a century or so there are no news about the building, which has become property of the Municipality, and that was used as a military laundry and disinfection place during World War I; simultaneously, the little house next door, which overlooks "vicolo Porta", becomes home of the "Night Asylum", founded in 1894. In 1920, the former Ottelio house was finally designated as the home of the Institute of Music. The first lessons took place in 1921, and the following year the building was customized, according to the new requirements. The simple sixteenth century architecture of Ottelio palace has nothing special, but the environment sorrounding it (the canal, the trees) and the clear measurability of its outlines make it look very fascinating. The most outstanding element is the three-light window with the two side arches and the central arch, complemented by a stone balustrade that, supported by four sturdy shelves, almost seems to smash the austere and simple portal below. Inside, there is a good sized central hall, nowadays called "Vivaldi concert-hall", with a Sansovino truss and leaded glass windows. The recent restoration works, completed in 1997, as well as restoring the building to its ancient splendor, have allowed the recovery of valuable archaeological finds, such as pieces of ceramic tableware, Renaissance glasses and a thousand fragments of slipped tiles, etched and painted, dating back to the sixteenth century.

da E. Bartolini - G. Bergamini - L. Sereni, Raccontare Udine. Vicende di case e palazzi, Udine 1983.